Cliff Notes

- I’m not saying you should consume bucket-loads of sugar 24/7 365

- Don’t promote fear mongering and misinformation. Especially if you’re not qualified to do so.

- Sugar-sweetened beverages are okay to consume in moderation provided you’re not overly sedentary and have a high-energy diet overall.

- Evidence is lacking in the obesity and sugar department.

- Fructose gets a bit of a bad rap for nothing. Increases in obesity continue to rise as consumption of fructose and refined sugar drop or continue to remain the same.

- When studies go for longer than 14 days sugar has little effect on plasma triacylglycerol (TAG) and non-esterified fatty acids (NEFA).

- After we eliminate confounding variables, there’s no relationship between sugar and certain types of cancer.

- All the macronutrients are good. You should eat food rich in all of them. Eat lots of fruits and vegetables and enjoy life.

Introduction

If there’s definitely one thing I’m sick to death of hearing in the fitness community it’s that sugar is bad for us and it lowers our immune system, gives us cancer, makes us fat and is stealing our girlfriends

Hide yo’ wife, hide yo’ kids, sugar is-a comin’

Just straight off the bat right now I’ll shut down 3 stupid myths;

Sugar does not lower our immune system. Athletes consume glucose to blunt the effects of catabolic hormones during long, high intensity endurance events and ENHANCE IMMUNE FUNCTION1

Sugar does NOT ‘give’ us cancer (quite frankly nothing really “gives” cancer to anyone). This comes from silly research showing that glucose fuels cancer cells. GLUCOSE FUELS THE FUNCTION OF ALL CELLS! Physiology 101. People who’ve done 200 minutes of intense web browsing on their phones are ignorant of simple physiological principles that underpin human structure and function. There’ll be more on cancer later in this article so keep reading!

Sugar is not making us fat – weight gain is multi-factorial. You cannot demonise one factor and be ignorant to the rest of them2. This is dangerous and could deter us from the bigger picture.

Before we can begin busting some more myths and going over why sugar isn’t fundamentally toxic, bad and/or ‘the white devil’ we need to go over the basics first.

Sugar – The Basics

All the information in this section comes from a text I purchased in second year university called ‘Understanding Nutrition’ which is still to this day my go to source for nutrition information. If you’re willing to understand more about nutrition you should probably invest in a copy. As for now. Let’s talk about carbs and sugar.

Carbohydrates are either simple or complex (sugars or fibre/starches). Monosaccharides are a single unit of sugar. Disaccharides are pairs of monosaccharides. The complex carbs are polysaccharides which are big molecules of chains of monosaccharides.

The simple carbohydrates include glucose, fructose and galactose, the simple monosaccharides. The three disaccharides are maltose (glucose and glucose), sucrose (glucose and fructose) and lactose (glucose and galactose).

Glucose is a large, complex molecule. Each carbon atom has four bonds, each oxygen atom has two bonds and each hydrogen atom has one bond. Fructose is the sweetest sugar and has the same chemical formula as glucose with a different chemical structure. Fructose is sweeter on the tongue due to its anatomical arrangement and it can be found in honey and fruit. Galactose is the last monosaccharide.

Glucose is part of all three disaccharides. The other member of the pair is fructose, galactose or another glucose. Condensation and hydrolysis occur and this chemical reaction puts together and takes apart the disaccharides. Maltose, Sucrose and Lactose are disaccharides.

Sugar-Sweetened Beverage

Right off the bat the evidence to suggest that sugar-sweetened beverages fuel the obesity crisis is flawed. They’re usually blamed for childhood obesity. Sugar sweetened beverages only account for 7% of total energy intake of children aged 2-163. Childhood obesity and sugar-sweetened beverage consumption are probably separate issues altogether or other elements are at work.

The first notorious ‘sugar is evil’ study that I usually see cited comes from Ludwig, Peterson, and Gortmaker4. Their research found that having too many sweet sugary drinks makes children obese. This is your typical nit-picked type of evidence. First off, the study only found an association between sugar consumption and obesity. Studies that are observational in nature cannot determine causality5. Children in this study exercised regularly (1-2 h / day). Exercise increases bone mineral density and muscle size and strength in children6. This may lead to gains in body mass. BMI was used to assess increases in obesity. Herein lies the biggest issue. You can’t control for puberty, exercise, sedentary behaviour, gains in lean muscle and overall development throughout growth. Using BMI to assess changes in weight has a plethora of confounding variables including not being able to assess gains in lean mass. It’s possible that the kids just got bigger because that’s what kids do – they grow. The authors even admit that;

“…there is no clear evidence that consumption of sugar per se affects food intake in a unique manner or causes obesity.”

The real conclusion of this study should be “over two years, kids end up growing.” Sugar-supplemented diets mainly from Sugar-Sweetened beverages have been reported to cause weight gain over a ten-week period. Raben et al supplemented diets with sugar but with a 3-fold difference in the amount of energy the supplements provided between sucrose and sweetener groups7. The difference in energy would more likely explain the weight gained, not the addition of sugar to the diet. Gains in body mass occur when energy in is greater than energy out. Clearly, sugar is not to blame here.

Poor, defenceless Fructose, added sugars and the modern western diet.

If there is one sugar that has copped it over the past few decades it’s fructose. It is the sweetest of all the sugars as mentioned previously, but because of poor research and certain fad-diets it’s become the most hated sugar of them all. According to a review conducted by White8 PubMed and Google Scholar list 1500 and 2600 publications with fructose in the titles since 2004. He goes onto cite work from Forbes and Bowman who suggest that we should consider all other macronutrients as part of the daily diet because we rarely consume fructose in its purest form. They go on to suggest most studies use fructose intakes that are beyond the estimated intakes and that if you consume any macronutrient in excess it’s bad for you. Glinsmann and Bowman9 suggest that there isn’t enough evidence to increase or decrease it in our food supply.

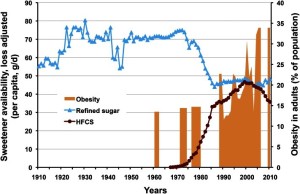

The modern western diet is high in calories and is usually combined with large amount of sedentary behaviour10. Sucrose intake increased 40% between 1910 and 1921 but then it levelled off after that8. Obesity still continued to rise.

This is a very important finding. There was a levelling off or decrease in the amount of refined sugar and fructose we’ve been consuming but we’re still getting fatter as a society. Clearly there are other factors at play here such as an increase in sedentary behaviour and overall energy intake11,12. Another very important point to make is that energy from caloric sweeteners was only 8% but energy from flour/cereal products and fat accounts for 90% of our total energy intake12. White goes onto cite work from Welsh et al who confirms that the amount of added sugar we consume has decline in children of all ages and people since 19998. It’s also common for people to suggest that fructose influence triglyceride levels in the body but this isn’t always the case. Fructose doesn’t cause changes in triglyceride or body weight when consumed at normal levels13. Tappy and Mittendorfer14 suggest that epidemiological studies usually don’t demonstrate that fructose or sugar are responsible for increases in energy or metabolic disease. Additionally, they go on to state;

“Public health policies to eliminate or limit fructose in the diet should be considered premature. Instead, efforts should be made to promote a healthy lifestyle that includes physical activity and nutritious foods while avoiding intake of excess calories until solid evidence to support action against fructose is available”

This seems like common sense, but unfortunately sometimes common sense isn’t always common sense.

Obesity, the metabolic syndrome, cancer and sugar

Sugar is usually blamed for the obesity crisis. More than 50% of adults and 30% of children in Western Society are obese and rates continue to rise15. Ruxton, Garnder, and McNulty examined sugar and obesity in their review. They found that most of the research compared high and low sugar diets. Results from research by Saris et al showed that sugar in diets didn’t obstruct weight management16. Three studies cited by Ruxton, Garnder, and McNulty found no positive correlation between sugar and obesity. Interestingly, research by Gibson17 found that the people with the lowest BMI had the most sugar in their diets. The authors propose;

“The finding that sugar and BMI were not positively correlated could be explained by the existence of a “fat-sugar seesaw,” implying that high sugar consumers eat fewer high fat foods.”15

People who consume lower intakes of fat probably consume less calories seeing as calories from fat are the most energy dense of them all (9kcal’s/g of fat).

Sugar is also commonly but wrongly blamed for increasing risk of metabolic syndrome or Syndrome X because it increases plasma triacylglycerol (TAG) and non-esterified fatty acids (NEFA)18. Ruxton, Garnder, and McNulty advocate that these changes are temporary and when studies go for longer than 14 days there is no association between lipid and sugar levels15. They also go onto note that people in these studies already had metabolic irregularities and were obese. They consumed a diet rich in sucrose and still didn’t see any long-term contrary metabolic effects.

In cancer and sugar studies it’s hard to determine a relationship due to confounding variables from total energy intake15,19. Glycaemic load (the amount of carbohydrates a food contains) is a major confounding factor amongst the cancer and sugar research. Ruxton, Garnder, and McNulty cite work from Hill and Caygill who review the evidence. They quantified associations between colorectal cancer risk and dietary factors. When total energy and glycaemic load weren’t involved, there was no relationship between sugar and colorectal cancer15.

Conclusion

I’m not saying you should consume bucket-loads of sugar 24/7 365 but now that you understand the basics of sugars and carbohydrates and the limitations amongst most of the nit-picked research I hope you use your new-found knowledge for good instead of evil. Don’t promote fear mongering and misinformation. Especially if you’re not qualified to do so. Sugar-sweetened beverages are okay to consume in moderation provided you’re not overly sedentary and have a high-energy diet overall. Evidence is lacking in the obesity and sugar department. Fructose gets a bit of a bad rap for nothing. Increases in obesity continue to rise as consumption of fructose and refined sugar drop or continue to remain the same. When studies go for longer than 14 days sugar has little effect on plasma triacylglycerol (TAG) and non-esterified fatty acids (NEFA). After we eliminate confounding variables, there’s no relationship between sugar and colorectal cancer.

All the macronutrients are good. You should eat food rich in all of them. Eat lots of fruits and vegetables and enjoy life.

1 Nieman, D. & Pedersen, B. Exercise and Immune Function. Sports Medicine 27, 73-80, doi:10.2165/00007256-199927020-00001 (1999).

2 Grundy, S. M. Multifactorial causation of obesity: implications for prevention. The American journal of clinical nutrition 67, 563s-572s (1998).

3 Hector D, R. A., Louie J, Flood V, Gill T. Soft drinks, weight status and health: a review., <http://www.natcen.ac.uk/media/175123/national-diet-and-nutrition-survey-years-1-2-and-3.pdf> (2009).

4 Ludwig, D. S., Peterson, K. E. & Gortmaker, S. L. Relation between consumption of sugar-sweetened drinks and childhood obesity: a prospective, observational analysis. Lancet 357, 505 (2001).

5 Carlson, M. D. A. & Morrison, R. S. Study Design, Precision, and Validity in Observational Studies. Journal of Palliative Medicine 12, 77-82, doi:10.1089/jpm.2008.9690 (2009).

6 Maggio, A. B. et al. Physical activity increases bone mineral density in children with type 1 diabetes. Medicine and science in sports and exercise 44, 1206-1211, doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182496a25 (2012).

7 Raben, A., Vasilaras, T. H., Moller, A. C. & Astrup, A. Sucrose compared with artificial sweeteners: different effects on ad libitum food intake and body weight after 10 wk of supplementation in overweight subjects. The American journal of clinical nutrition 76, 721-729 (2002).

8 White, J. S. Challenging the fructose hypothesis: new perspectives on fructose consumption and metabolism. Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md.) 4, 246-256, doi:10.3945/an.112.003137 (2013).

9 Glinsmann, W. H. & Bowman, B. A. The public health significance of dietary fructose. The American journal of clinical nutrition 58, 820S-823S (1993).

10 Scully, M., Dixon, H., White, V. & Beckmann, K. Dietary, physical activity and sedentary behaviour among Australian secondary students in 2005. Health Promotion International 22, 236-245 (2007).

11 AUSTRALIAN IDLE: PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND SEDENTARY BEHAVIOUR OF ADULT AUSTRALIANS, <http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/4156.0.55.001Main+Features4Nov%202013> (25/11/2013 ).

12 Swinburn, B. A. et al. Estimating the changes in energy flux that characterize the rise in obesity prevalence. The American journal of clinical nutrition 89, 1723-1728, doi:10.3945/ajcn.2008.27061 (2009).

13 Livesey, G. Fructose ingestion: dose-dependent responses in health research. The Journal of nutrition 139, 1246s-1252s, doi:10.3945/jn.108.097949 (2009).

14 Tappy, L. & Mittendorfer, B. Fructose toxicity: is the science ready for public health actions? Current opinion in clinical nutrition and metabolic care 15, 357-361, doi:10.1097/MCO.0b013e328354727e (2012).

15 Ruxton, C. H. S., Gardner, E. J. & McNulty, H. M. Is Sugar Consumption Detrimental to Health? A Review of the Evidence 1995—2006. Critical Reviews in Food Science & Nutrition 50, 1-19 (2010).

16 Saris, W. H. et al. Randomized controlled trial of changes in dietary carbohydrate/fat ratio and simple vs complex carbohydrates on body weight and blood lipids: the CARMEN study. The Carbohydrate Ratio Management in European National diets. International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders : journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity 24, 1310-1318 (2000).

17 Gibson, S. A. Are diets high in non-milk extrinsic sugars conducive to obesity? An analysis from the Dietary and Nutritional Survey of British Adults. Journal of human nutrition and dietetics : the official journal of the British Dietetic Association 20, 229-238, doi:10.1111/j.1365-277X.2007.00767.x (2007).

18 Daly, M. E. et al. Acute effects on insulin sensitivity and diurnal metabolic profiles of a high-sucrose compared with a high-starch diet. The American journal of clinical nutrition 67, 1186-1196 (1998).

19 Favero, A., Parpinel, M. & Franceschi, S. Diet and risk of breast cancer: major findings from an Italian case-control study. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie 52, 109-115, doi:10.1016/s0753-3322(98)80088-7 (1998).